Because the twenty-year-old Stella Liebeck case is getting another round of attention on some blogs — Susan Saladoff’s short film Hot Coffee having served quite successfully to keep the trial lawyers’ side of the controversy in circulation — it’s worth a closer look at the latest in Jim Dedman’s (Abnormal Use) writings deflating the case’s mythos [Defense Research Institute DRI Today, previously briefly noted in a roundup a couple of weeks ago]. Excerpt:

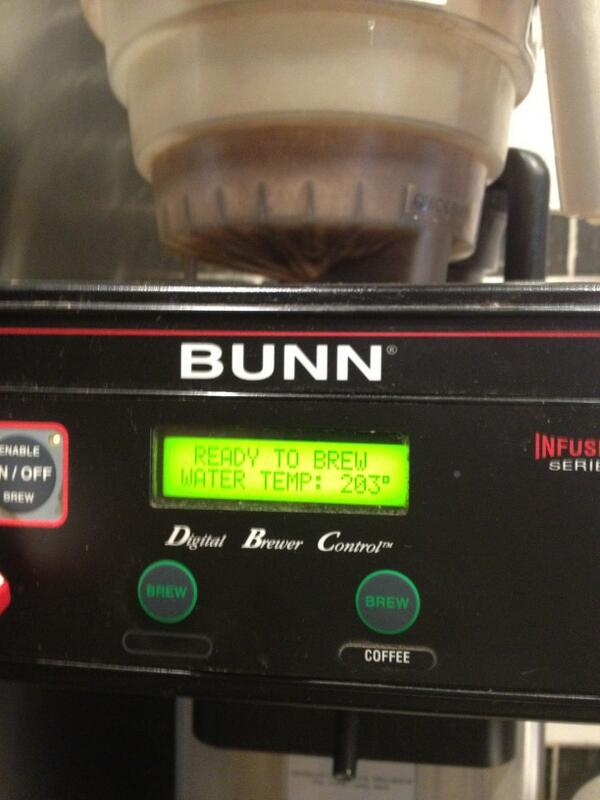

The central issue was whether hot coffee, which by its very nature is hot, is an unreasonably dangerous and defective product because of its temperature. More specifically, the case concerned whether coffee served at 180-190 degrees is so hot that it makes the coffee itself unreasonably dangerous and defective. Shortly after the trial, The Wall Street Journal reported that McDonalds’ internal manuals at the time–produced in the litigation— indicated that “its coffee must be brewed at 195 to 205 degrees and held at 180 to 190 degrees for optimal taste.” … Contemporary media reports suggested that the coffee was approximately 165 to 170 degrees at the time of the spill, indicating that it had cooled somewhat between the time it was served and the time it had spilled….

Interestingly, today, on its website, the National Coffee Association advises that “[y]our brewer should maintain a water temperature between 195–205 degrees Fahrenheit for optimal extraction” and that “[i]f it will be a few minutes before it will be served, the temperature should be maintained at 180–185 degrees Fahrenheit.” Even in 1994, the National Coffee Association confirmed that McDonalds’ serving temperatures were within industry guidelines (and many restaurateurs have found that their customers complain if they lower the temperature of their coffee).

Failure to warn was also one of the theories in the case:

Curiously, the warnings issue receives little attention these days. Although Liebeck alleged that “the container that it was sold in had no warnings, or had a lack of warnings,” the very cup at issue is prominently displayed—with its “Plaintiff’s Exhibit 44” sticker still affixed—on both the website and the promotional poster of the Hot Coffee film. However, in the very same pictures, it is clear that the cup advises in orange text: “Caution: Contents Hot.”

Earlier coverage here, etc., etc., as well as by Nick Farr at Abnormal Use and Ted Frank at Point of Law. (Yet more: index of Abnormal Use posts).

P.S. It might be added that those “everything you know about the Stella Liebeck case is wrong” internet memes are very often wrong themselves. In particular:

* The story got onto national wires via the AP and immediately set off widespread public discussion on the strength of its own inherent interest, with no evident push from any interest group. When an organized public relations effort did emerge in early weeks of discussion, it was from the plaintiff’s side, which held a press conference in Washington seeking (successfully) to establish and solidify themes in Liebeck’s favor, such as that there had been many earlier consumer complaints about McDonald’s coffee temperature.

* The most gripping supposed “myths of the Liebeck case” were not in fact widely asserted or circulated either at that time or since. Very few commentators erroneously asserted that Liebeck had been driving or that her car was moving, or (even worse) mistakenly claimed that her injuries were somehow minor. Only by treating stray outliers as somehow representative of public discussion can revisionists portray the public’s grasp of the case as grossly ill-informed. It was then and is now plausible for both laypersons and experienced lawyers to fully and accurately grasp the facts of the Liebeck case and, based on that understanding, sharply disagree with the New Mexico jury’s verdict in her favor. That’s one reason most American juries both before and since 1994, asked to decide hot-beverage lawsuits based on similar fact patterns and claims, have decided for the defense even where serious injuries might engage sympathy for a plaintiff’s situation.

* Meanwhile, some truly extraordinary myths and misconceptions — such as that McDonald’s somehow mysteriously “superheated” its brewing water to temperatures unknown in home teakettle use — have widely circulated on the internet in years since, advanced by lawyers and even professors who have every reason to know better. Peculiar assertions of this sort seldom get attention in the oft-seen “myths of the Liebeck case” internet genre.

Filed under: hot coffee, Stella Liebeck